We are talking a lot about mental health and associated stigma. The consensus seems to be that mental health stigma is on the run, especially when we talk about workplace mental health. I’m not so sure. I found myself asking, how far have we come with mental health stigma?

Roughly 25 years ago I got a call from my mother. “It’s your dad. He’s in the hospital, and he’s crazy and I don’t know what to do.” It was clear I wasn’t going to figure it out from 900 miles away, so 16 hours later I walked into a hospital room and found my father delirious and talking nonsense. Gradually I pieced together that he was furious because he was convinced my mother had sold their house and all their belongings so that she could send him to Germany to a prison camp, where they were going to lock him up. In that moment he was convinced he was in fact in a prison camp, being held against his will. He wasn’t sure about me.

I knew by now that my dad had fallen and hurt his hip. It wasn’t broken, but it was very painful and radiating to his back. When I heard his story, I knew what else had happened, so I asked to speak with his doctor. A resident arrived, full of airs, and I said, “You have to stop his narcotics right away.” With bare tolerance, he asked, “why would I do that?” I replied that my father’s unusual reaction to narcotics was to hallucinate and become delirious.

“But he’s in pain! What am I supposed to do about his pain?”

My response seemed to catch him off guard: “Do you imagine that it isn’t painful for him to believe that his wife sold all their belongings so that she could send him to a prison camp in Germany? Do you imagine that’s somehow less painful than his hip will be if you stop the medication??” I might have raised my voice by the end of that. Maybe just a little.

After rousting the attending (me: “I don’t care if you wake him up”), the order was written, and 14 hours later my dad was surprised to see me and told me his hip hurt but that he’d had the most terrible dream …

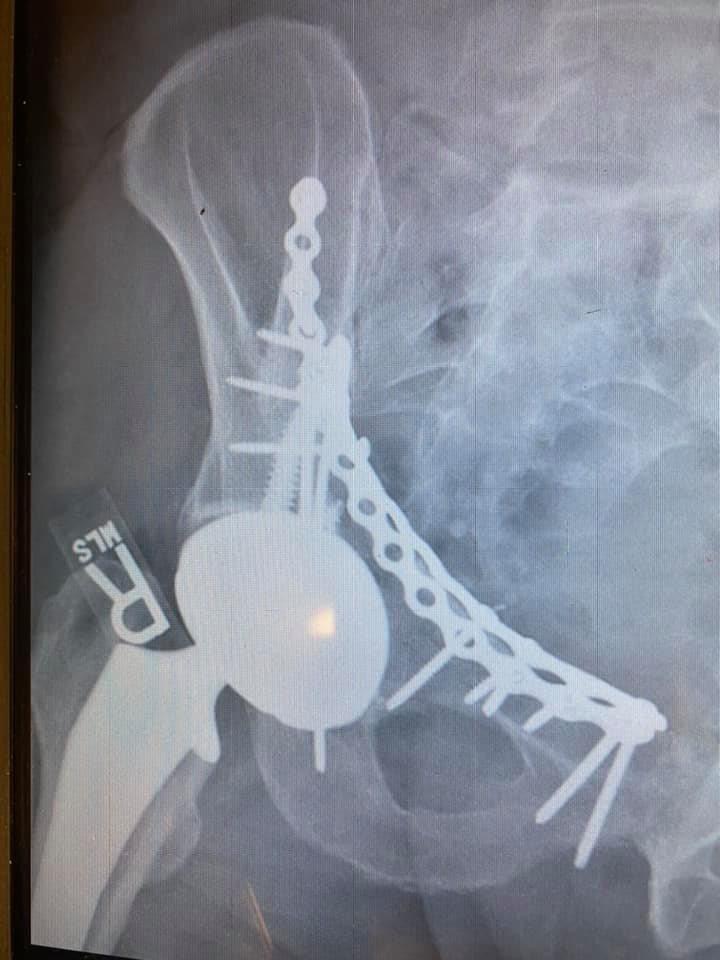

Fast forward 26 years. Two weeks ago, riding my bike on a glorious day and celebrating the end of one job and excited about starting a new one, I hit a patch of wet leaves that were on moss and mold. The bike flipped out from under me, and I was instantly thrown hard onto the back of my right hip. Hard enough, it turned out, that I fractured my ilium (the main pelvic bone) clean through and pushed the head of my femur through the hip socket and out the front of it. It took 2 different surgical teams to put Humpty Dumpty back together in a 7-hour marathon (that x-ray is me, aka Humpty), but I am home rehabbing and able to tell the tale.

It’s fair to say that it hurt. A lot. Less after surgery than before, to be sure, but still a lot. As is expected practice, I was given some oxycodone to take for the pain when I went home.

But you see, like my dad, I have a bad reaction to opioids. He got psychotic. I, instead, if I take them regularly for more than 3 or 4 days, become suicidally depressed (for those of you who don’t know me, just trust me that it’s highly uncharacteristic). I know this because it happened a few years ago when I had partial knee replacements, and it scared me. I was determined to avoid a repeat.

I was telling an online acquaintance of my plan for rapid weaning (which worked, by the way), and he wrote,

“But you’re in pain! What are you going to do about the pain?”

I said without missing a beat, “Do you imagine that being suicidally depressed is less painful than my hip??”

Only then did I realize the connection between those stories. They are separated by 26 years, and yet they have identical themes that are at the core of the mental health “problem.”

During those 26 years, there’s been a slowly growing public awareness of the need for mental health care. More recently that trend has been hugely accelerated by the tsunami of people who describe the increased stresses of living in the time of COVID, job burnout, and new-onset (or newly recognized) anxiety and depressive disorders. We are all suddenly talking about the importance of mental health, and all that talking is being taken as evidence that the stigma of mental illness is, at last, being vanquished.

I say, not so fast. I’m glad we’re talking about it more, finally. FINALLY. But my stories demonstrate that talking alone doesn’t mean stigma is going anywhere. Because under that stigma is the belief that physical conditions and physical pain are “real,” and mental conditions and mental pain are not. Under the stigma is the belief that physical and mental health can somehow be separated and treated independently. That’s wrong and causing far too many problems for society, the healthcare system, employers, and individuals.

Until we see that we must address physical and mental health as a whole and that until we do, we will continue to relegate mental distress to second-class status. And anything that has second-class status is subject to stigma.

I’m very happy we are talking about mental health more, and that we are slowly chipping away at the stigma that is getting in the way. But the stigma of mental illness is alive and well and we must neither pretend otherwise nor celebrate too quickly. We have to address the underlying problems before things will really change, and that’s going to take some very real creativity and some very hard work.

Who’s with me?

Dr Les Kertay

One comment